CANNABIS TINCTURES AND FLUID-EXTRACTS

Chapter 4

Chapter 4

Technically speaking, a TINCTURE is nothing more than an alcohol-base liquid mixture.

Tinctures are useful as they can be used to liquify oil-based substances, like Medical Cannabis, which like any other oil base substance, doesn't mix too well in water-base mixtures.

Evans |

Eli Lilly |

Lloyd's |

ParkeDavis |

SharpDohme |

Frosst |

Bickford |

Evans |

Willow |

boerickeTafel |

|

Eli-Lilly |

Drug Syn |

Schaffelin |

Mulford |

Merrell |

Bottle-Mold |

bottleTop |

Lloyd Label |

Lloyd Label |

LloydLabel |

4.1 - CANNABIS TINCTURES AND FLUID-EXTRACTS:

4.1.1 - TINCTURES:Technically speaking, a TINCTURE is nothing more than an alcohol-base liquid mixture.

Tinctures are useful as they can be used to liquify oil-based substances, like Medical Cannabis, which like any other oil base substance, doesn't mix too well in water-base mixtures.

4.1.2 - FLUID-EXTRACTS:

Although the chemistry escapes many of us, including the author, while Cannabis will NOT mix directly with water: Once it has been liquified into a Tincture, then it will. Add enough water, or any or any other diluting agent to thin it down and soon it is not longer considered a Tincture, but a Fluid-Extract.

For Antique Collectors however, a great deal of confusion exists distinguishing the difference between the two. As both products were packaged in similar looking bottles, with similar looking labels, this should come as no surprise.

For simplicity, this book classifies both of them as tinctures. The antique collector, however, should be aware that there is a difference.

4.1.3 - HISTORICAL TINCTURES:

The use of Cannabis by Western Medicine goes all the way back to the days of Galan (a writer of Medical Books) and the Roman Empire. However its use seems to have been very limited and applied only to minor medical uses.

However, all that would change in 1839, with the publication of an article "On The Preparations of the Indian Hemp, or Gunjah"[1] by Dr. Walter O'Shaughnessy,[2] who at the time was a young but already well know physician residing in India.

Most historians agree that it was O'Shaughnessy, who more than anyone else, helped publicize the medical uses of Cannabis. He had learned about Cannabis, while in India (from Mohammedan and Hindu physicians), and upon returning to England, quickly went about lecturing about the subject. Not only did he talk about its medical uses, but also lectured about its pharmaceutical preparations and manufacturing techniques.

Tinctures, of and by themselves, were nothing new at the time. They had been in use by Western Medicine for centuries before than. What was new, and only introduced after O'Shaughnessy was the use of Cannabis in their preparation. For antique collectors, this means that Cannabis Tinctures first began to make their appearance around 1840, but were soon very, very common. Not only did it make its way into Brand/Trade name products, but it also became common practice for apothecary shops to manufacture their own tincture.

[See Chapter 3 on Apothecary Jars/Bottles]

4.1.4 - CANNABIS TINCTURES, THEIR USES:

The main use of Tinctured Cannabis seemed to be in the manufacture of compound drugs, which made of Cannabis only as one of many ingredients. This seems to be the case, simply because liquified Cannabis was easer to use in such mixtures.

The Tincture itself, was prescribed by Doctors directly[3] for numerous ailments---Usually as so many drops of Cannabis Tincture, diluted in a quarter cup of warm water etc.

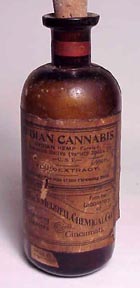

Cannabis was used to treat so many ailments[4] that almost ALL pharmaceutical manufacturers had their own Brand-Named Cannabis Tincture bottles. This is good news to antique collectors, as many of these old bottles are still in existence.

However, at least in the first half of the 19th Century, most Tinctures were NOT being manufactured by established pharmaceutical companies, but by local apothecary shops throughout the country. And, while no actual statistics exist, it is safe in say that the apothecary shop that did not manufacture its own Cannabis Tinctures was the exception rather than the rule.

Remember at that time Industrial Hemp was legally being grown and thus Cannabis, as a by-product, was easily obtainable. In fact, it is amusing to read some of the old pharmaceutical journals from the 1880s. One group of articles -- quite a spirited debate, written by well-known pharmacists of the day, dealt with the exact color of the "Tincture Cannabis" and why or why not, it was a deep green. (Dr. Squibb of Squibb Pharmaceuticals won, and it was a deep green). But what strikes most readers as odd, is that the articles themselves did not bother to write down exactly HOW the tinctures were actually being manufactured. It was just assumed that the druggist already knew how to make them and had been doing so for some time.

4.2 - THE MANUFACTURE OF TINCTURES:

The methodology needed to manufacture Cannabis Tincture products was relatively simple and well understood by nearly all 19th Century Druggists. Any reader of the U.S. Pharmacopoeia [see Appendix B] could obtain the needed manufacturing details and specifications. And while these specifications would change from time to time, as technology and knowledge of medical properties increased, generally the process consisted of nothing more than taking the dried flower tops of the hemp plant and brewing them (just like coffee or tea) in a percolator to extract the oily resin concentrate. Once the active medical ingredient was obtained, it would than be mixed with alcohol to liquefy and homogenize the tincture.

The process was so simple that for the first part of the 19th Century "Tincture Cannabis" was the domain of the local apothecary shop. But all of that would soon change.

By the late 19th century, Brand-Name drugs slowly began to replace locally (apothecary shop) made products. People really wanted the security and presumed superior quality that only a "Brand-Name" could give them.

As an example, the Cannabis Tincture used by the great American writer Fitz Hugh Ludlow (who wrote much-quoted articles about his experiences with Cannabis) was a brand name product manufactured by Tilden & Company of New Lebanon, New York. Without question, he could have bought a much cheaper, locally made product, but chose instead to use a well known Brand-Name product.

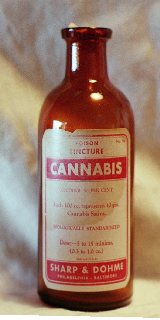

Below is a partial list of pharmaceutical manufacturers (most still recognizable today) of "Cannabis Tincture":

- H.K. MULFORD LABORATORIES (Today a part of Merck & Co.)

- ABBOTT LABORATORIES

- PARKE DAVIS & COMPANY (today known as Pfizer, Inc.)

- ELI LILLY AND COMPANY

- SQUIBB & SONS (today known as Bristol-Myers-Squibb)

- WILLIAM S. MERRELL CHEMICAL COMPANY (today known as American Hoechst Corp.)

- LLOYD BROTHERS (today known as American Hoechst Corp.)

- JOHN WYETH & BROTHER COMPANY (today known as American Home Products)

- MERCK & COMPANY

- SHARP & DOHME (Today a part of Merck & Co.)

- TILDEN & COMPANY

- UPJOHN CO.

- SCHIEFFELIN & CO.

4.3 - FROM APOTHECARY TO BRAND-NAME TINCTURES:

There were numerous reasons for the switch from local apothecary shop made, to Brand-Name products manufactured by large pharmaceutical companies.

In the early part of the 19th Century, the high cost of glass containers made pre-packaged products prohibitive. But by the late 19th Century, the machinery and manufacturing techniques had lowered their prices to the status of disposable items.

In addition, at the time there was a commonly held misconception[5] that Medical Cannabis grown in India was somehow superior to the domestic product. Major pharmaceutical houses were able to buy large lots of imported Indian Cannabis, which local druggists simply could not.

Also, economics of scale were soon working in favor of the large pharmaceutical houses. The local corner drugstores simply couldn't compete, and began to see their role as merely a retailer.

But by far the largest reason for the rise of brand-name products was their consistent quality. People simply began to distrust locally [almost home made] products that would vary from batch to batch.

4.4 - CASES OF CANNABIS POISONING --- THE MYTH:

Before going further, we must deviate into a myth --- But BEWARE, some myths die-hard. According to some, in the late 19th Century, numerous cases of poisoning by "Cannabis Indica" (Tincture or otherwise) were taking place. And in truth, the medical Journals[6] of their day were carrying more than their fair share of "Poisoning by Cannabis" articles.

This author has spent numerous hours in old medical archival libraries reading as many of such articles as possible. Here are the facts as I see them:

- Of all the post-1970 English-language medical journals that that the museum has been able to get a hold of, there have been no more than a couple-of-dozen actual documented cases of Cannabis poisoning. Given the extensive use of references and footnotes by the authors, in which no mass cases were reported, I feel confident that this number constitutes the sum total number.

- Of these cases, at least half of the poisonings were deliberately done by doctors as part of their research. (And here it should be noted that one of the ultimate purposes of these experiments seems to have been to obtain the data on which to base the article in the first place.)

- At least two of the articles -- again, in the authors' personal opinion -- are nothing more than fanciful works of fiction.

- Of the remainder, half seem to be what we can term real victims, while the other half (at least from what I have been able to ascertain) are what we would term, in today's world, walking accidents waiting to happen; total royal losers who would take an overdose of anything and were only lucky it was Cannabis and not aspirin or some other less merciful substance.

- No one has ever died as a result of an overdose of Cannabis.

- Pharmaceutical giant Parke Davis & Co. even purposely tried to kill some dogs without any luck, Abbott Labs did succeed in killing a rabbit, however it was possible that the death was caused by other factors.

- After much study, It was finally estimated that the oral dose required to kill a mouse is 40,000 times the normal dose required for medical purposes.

- The antidote for Cannabis poisoning, which was accepted by the medical establishment at the time was;---- "COFFEE."

It would not be until the late 1890's that a consortium of pharmaceutical houses (something illegal today), led by Parke-Davis & Co. and Eli Lilly, would develop a crude but effective physiological testing method (by using dogs) to standardize the strength of their tinctures. By the 1910s, reports of cannabis poisoning had all but disappeared from the medical journals.

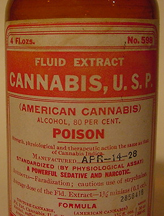

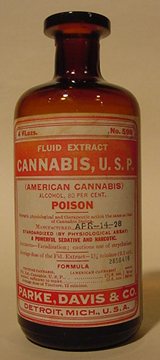

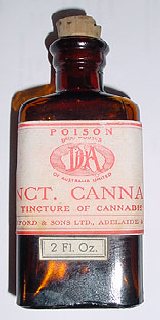

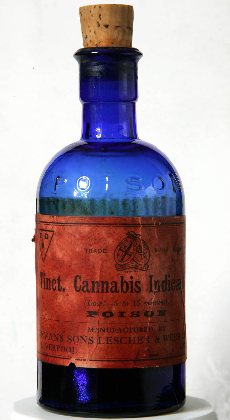

4.5 - PARKE-DAVIS BOTTLE: [See Pictures]

For numerous reasons this Parke-Davis Cannabis Fluid-Extract Bottle has become the most famous and most sought after of all Cannabis antique bottles -- literally the pride of any collection. In mint condition, it can command between $1,000 and $5,000. And well it should, it literally represents the height of botanical medical technology in many ways.

4.5.1 - PARKE DAVIS-- WHAT THE LABEL TELLS US: [See Pictures]

First, notice the manufacturers date code of April 14, 1928. At a time when expiration dates on products were virtually unheard of, this is quite a revelation. Obviously, the manufacturer was trying to say, "This product has a shelf life -- Do Not Exceed It."

Next notice the emphasis on the words "American Cannabis" (AKA Cannabis Americana), after which the label goes on to say, "Therapeutic action the same as that of Cannabis Indica." This was because so many people held the belief that Cannabis that was grown in British India was superior to that grown in America.[5]

In accordance with the federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, in addition to Cannabis the label also mentions the amount of alcohol (80%) used. As oil (Cannabis is an oil based substance) and water do not mix, the alcohol was needed to form the base of the fluid-extract. Also, note the letters, U.S.P., which indicate that this product was made up to United States Pharmacopoeia standards [see Appendix C].

Now notice the clearly visible word "Poison," which (as explained elsewhere) is a misnomer. Despite the fact that NO ONE has ever been known to die from its use, many states and government agencies still required that the word be placed on the label. This contradiction in terms sometimes leads to humorous situations. For instance, notice the lack of any mention of an antidote (which by the way is coffee) on the label. One would expect a reputable pharmaceutical house like Parke-Davis, which even lists its manufacture date, to have listed an antidote for POISON. But, can one imagine such a label?

- Warning Poison:

- Number of people that die each year = 0

- Antidote = Coffee

Last of all, look at how much emphasis has been placed on the words "Standardized By Physiological Assay." It must be remembered that this was the age of generic drugs, and each pharmaceutical house sold essentially the same drugs that all others did. What they were actually selling was a set of quality and manufacturing standards.

It cannot be emphasized enough that most of the early problems associated with Cannabis (and other botanical pharmaceuticals as well) were caused by the variations in strength or potency between one batch and the next. Someone rightfully described it as a pharmaceutical crapshoot.

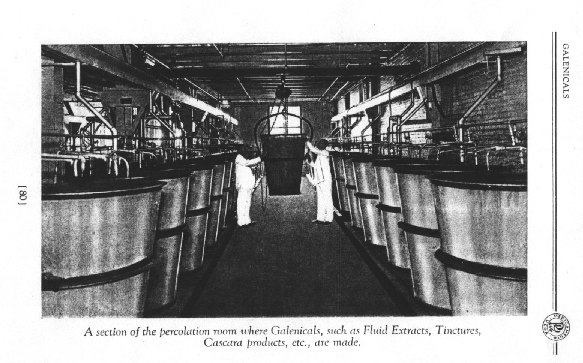

However, by the late 19th Century, Parke-Davis (along with other pharmaceutical houses) started using physiological testing to assure consistency. Dogs would be given samples of the product as it was being manufactured, and their bio-signs monitored. (Note: No dogs ever died as a result). The make-up of the fluid-extract, which was being manufactured in large beer-vat like containers [See Picture] would than be adjusted accordingly.

Picture: Taken from 1929 Parke-Davis product catalog.

Only after a pre-set consistency could be assured did they begin to bottle the product. By 1928, when this bottle was made, that the label was able to state:

-

"Average dose of the Fluid-Extract -- 1 1/2 minims (0.1cc),"

4.5.2 - THE COLOR OF THE BOTTLE: Studies conducted by major pharmaceutical houses in the early part of the 20th Century showed that when exposed to air and sunlight, Cannabis Indica, losses half it's medical strength every three years.

Thus in order to preserve the potency of their product, most pharmaceutical manufacturers began using dark-color bottles as protection against sunlight.

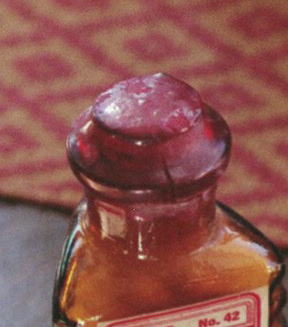

4.5.3 - SEALING THEIR PRODUCTS: [See Pictures]

Because all botanical drugs lose potency when exposed to air and sunlight, by the early 20th Century pharmaceutical companies were doing their best to protect and isolate their products from both. These pictures show the steps taken by Parke-Davis to (virtually) hermetically seal their products.

Either Bee's wax (left) or a plastic like substance (right) was used as a coating around the cork.

4.6 - WHAT THE BOTTLE SEAM TELLS US: [See Pictures]

1840 - 1860* Seam verily goes over the shoulder |

1860 - 1880 Seam rises onto the neck of the bottle |

1880 - 1900 Seam completely goes up the neck |

After 1900 Seam rises completely to the top of Bottle |